Astronomers from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey release SDSS-III, the most detailed picture of the universe ever made

Share Comments (…) Alok Jha, science correspondent guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 11 January 2011 18.30 GMT larger | smaller Article history

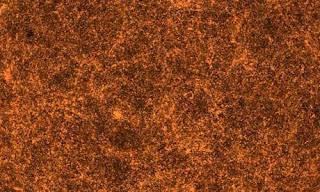

A fragment of Sloan Digital Sky Survey-III (SDSS-III) showing walls and clusters of galaxies visible from the southern hemisphere. Photograph: SDSS-III/PA It is the culmination of a decade spent scanning the night skies and would take half a million high-definition televisions to view at its full resolution. With more than a trillion pixels, this is the most detailed digital picture of the universe ever produced.

It replaces an image that is now over half a century old, created on photographic plates by the Palomar Sky Survey in the 1950s but still used by astronomers today.

By contrast, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey's third and final release of data (SDSS-III) was created using a 138-megapixel camera attached to a 2.5 metre telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. It contains 10 times as many objects – such as galaxies, stars and nebulae – as the Palomar survey and scientists hope it will be used for decades to come by astronomers hunting for everything from dark matter to planets orbiting other stars.

"There are half a billion objects detected in this image," said David Weinberg, an astronomer at Ohio State University who worked on the SDSS image. "About a quarter of a billion stars and a quarter of a billion galaxies."

Each pixel contains data in five different colours of light. "That's green, yellow, red, redder than red and bluer than blue. We actually take five different images of each piece of the sky, looking through different filters," said Weinberg.

Each pixel is about one-three-trillionth of the sky, and overall the image covers around a third of it. "The way the telescope works, it takes its images in long stripes so that in one night it will get one big long stripe. That's why there are two big patches that are all filled in and then there are these other stripes coming out of it which are the other places where we extended into other parts of the sky but didn't fill everything in."

Click to expand the picture above. At the bottom is a map of the whole SDSS image, split into the views of the northern and southern hemispheres of our galaxy. At this scale, huge structures such as clusters and walls of galaxies become visible. At the top left, a fraction of the sky visible from the southern hemisphere has been blown up to reveal a spiral-armed galaxy called Messier 33 (M33). This galaxy is 2m light years away from our solar system and is spotted with nurseries where new stars are being created – visible as green dots throughout its arms.

"Those green filaments are hydrogen gas that is being lit up by the hot stars in the middle," said Weinberg. "And there's a lot of blue stars in the image that are all young, hot stars that are formed in this galaxy."

At the top right is a further close-up of one of these star nurseries in M33, called NGC604.

For the brightest million objects in the survey, the SDSS team also measured the full spectra of the light, effectively passing the radiation through a prism and splitting it into different frequencies. This allowed the scientists to measure the distance to the objects, which was then used to infer a 3D map of their distribution.

"The goal is to understand why the expansion of the universe is speeding up – that is the biggest puzzle in cosmology today, because all of our experience is that ... things fall towards each other," said Weinberg. "But, at the scale of the universe, gravity seems to be pushing things apart. In addition, we're monitoring the motions of about 10,000 stars to try to detect them wobbling back and forth to see if they're being orbited by giant planets."

The SDSS data and images were released today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle. The 138-megapixel imaging camera that was used to take the millions of pictures that make up the latest image is being retired, destined to become part of the permanent collection at the Smithsonian in Washington DC – a recognition of its unique contribution to astronomy.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario